Harrison D. Ingles, Daddy, was born in Portsmouth, Ohio on April 27, 1894.

Growing Up

I don’t believe that my father’s family were poor. A lot of his early experiences were a result of the times in which he was born. At the turn of the Twentieth Century, education didn’t seem to be a top priority.

As far as money goes, my grandfather had a decent job and also owned a small grocery store. Daddy told me that around 1910, a man could raise a family on eleven dollars a week. And then he said, “My dad made seventeen, we were all right.”

At the age of twelve and having a sixth-grade education, Daddy quit school and took a job at a shoe factory. Ten hours a day and a half day on Saturday, fifty-five hours a week. His job was lacing shoes.

Daddy was paid a nickel an hour, $2.75 a week. He kept 75 cents and gave two dollars to his mother.

I don’t know much more of Daddy’s early years. Except for the fact that Daddy had a great love and respect for his father.

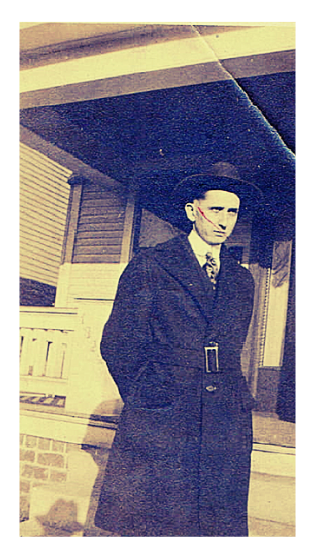

My Grandfather Ingles, born in 1861 and died in 1927.

It is my understanding that my Grandfather Ingles was a rather formidable man. The photograph, taken around 1920, tends to substantiate that.

21st Birthday

Daddy told me a couple of amusing stories about his 21st birthday, April 27, 1915. He had to laugh as he was relating the stories.

At midnight, the beginning of April 27, Daddy’s sister, Maggie, screamed out, “There’s a man in the house!”

Daddy ran downstairs. He was standing in the middle of the living room in his BVDs, wielding a pocket knife, and saying, “Where is he?”

The lights went on and the rest of the family laughed about the new “man in the house”.

The morning of his birthday, Daddy and his father went fishing in the Ohio River. Daddy told me that he caught the biggest catfish he had ever reeled in.

Later that day, my grandfather took Daddy to a little bar and said to the bartender, “Give my son a drink, he’s a man today.”

The bartender looked at Daddy and said, “Harrison, you little son of a bitch, you’ve been lying to me for four years.”

World War I

Daddy told me that, prior to America’s entry into World War I, he had found a job in upstate New York making artillery shells. The pay was per shell produced. Daddy told me that one man could not operate two lathes but two men could operate three. He found another man and the two of them operated three lathes. Daddy told me it was the most money he had ever made in his life.

One day, Daddy received a letter telling him that he was to go back to Ohio to be drafted into the Army.

Daddy sent his father a telegram saying that he was making too much money and he wasn’t going anywhere.

Daddy received a telegram from his father telling him to come home and get in the Army.

Daddy didn’t seem to pay much mind to President Wilson but he always listened to his father. Daddy went back to Ohio and became a soldier.

Daddy spent time in the trenches in World War I.

Daddy referred to his exalted rank as, “Buck ass private”.

By the way, I have a 1918 Christmas card that Daddy sent to his parents while in France.

Marriage

Daddy met Mama in 1919.

On my website, I have a blog I call “A Love Letter” and it is dated January 4, 1920. To me, the letter is amazing because it was written by a man with a 1906 sixth-grade education. I cannot imagine a man with a 2006 sixth-grade education composing such a letter. For that matter, a recent high school graduate.

Daddy married Mama on December 15, 1920. Daddy was 26 and Mama 21. I have their marriage certificate hanging on my office wall.

Some Good Times and Much Rough Going

In the 1920s, Daddy was an A&P store manager and Commander of the local American Legion Post in Middleport, Ohio.

My older sisters told me that Daddy was always bringing them candy and other treats. Daddy played poker with the mayor and chief of police. Times were good.

As an aside, Daddy told me that he, the mayor, and the chief of police always had a few drinks when they played cards. Nothing exceptional except that this was during Prohibition.

Because of the Great Depression, the 1930s were difficult times. Work was hard to find. I don’t believe that Daddy ever fully recovered. During the Great Depression and following, Daddy never really had much of a job. He took the work he could find.

In 1937, Mama and Daddy lived in Huntington, West Virginia. That year there was a devastating Ohio River flood. Record flood levels. Mama and Daddy lost almost everything. And one must remember that the country was still in the midst of the Great Depression.

Given all of the difficulties, Mama and Daddy still managed to raise my family and ensure that we all had a high school education. We always had shoes and clothes and a roof over our heads. We always ate. More potatoes and gravy than meat, but we ate.

By the way, three of us are college graduates.

Daddy always liked a drink but his drinking increased. When I was growing up, Daddy was drinking but he never allowed booze to keep him from work; he never missed a day and he went to work sober.

In 1947, Daddy found work as an attendant in the Huntington veterans hospital. He retired from that job in 1960.

A note here. In 1947, Daddy was 53 years old. He had very bad varicose veins. He had back problems from an old accident. From where we lived to the veterans hospital was at least eight miles. And the hospital sits on top of a steep hill. Daddy walked the distance to apply for the job because he didn’t want to spend the small bus fare.

The job of hospital attendant is a strenuous job and the man hiring at first denied the job to Daddy because of his age and physical problems. But when the man discovered that Daddy had walked that distance and climbed that hill to apply for the job, Daddy was hired. Think about that.

Children

I have six sisters and I am the youngest.

I will say no more on this subject because I have already written an article about my sisters, “Sisters, Sisters Everywhere.”

Daddy and I

My father was forty-five when I was born.

During World War II, Daddy found a job in a prisoner-of war camp in Baltimore. He didn’t make enough money to move the family to Baltimore, so he sent as much home as he could.

After the War, Daddy worked a 3:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. shift at the veterans hospital. And his days off were in the middle of the week. And, to be honest, he would have a few drinks when he wasn’t working.

What I am saying to you is that I never really got to know Daddy until I was a member of the U.S. Air Force (1958-1962).

But that is not to say Daddy ignored me, we just didn’t have much time together when I was young. But I have memories.

When I was six, Daddy taught me how to play the card game cassino. That game taught me to quickly look at card combinations and add them. For example if you are holding a nine and there is a four, a three, and a two on the board, you can pick them up. In other words, Daddy taught me how to quickly look things over, think, add, and count. As a matter of fact, Daddy and I played cassino together for many years, almost until the time of his death.

When I was seven, Daddy taught me how to play poker. That was a great lesson. It did me well while living in USAF barracks.

When I was eight, Daddy took me to a traveling carnival that came into town. We walked around and looked at the sights. I well remember the “tattooed lady”. She was, what you might say, a bit obese, which means she had a lot of room for tattoos. She was wearing a one-piece bathing suit. On the upper portion of her back was a map of North America. She invited the crowd to come inside and take a look at South America for only one thin dime. Sounded good to me. I said, “Let’s go in, Daddy.” Daddy looked down at me and said, “I don’t think so, son.” I have never forgotten that.

You know, Daddy never preached. He taught me things by either telling a story or saying something to make me think.

When I was in grade four, I said, “Daddy, I hate geography.” Daddy didn’t preach to me not to hate it. He responded, “Son, there isn’t a general in the Army who doesn’t know geography.” I got it. Geography is important.

When I was fourteen, I found a part-time job and I could still go to school. When I told Daddy about it, he was against it. He said, “Son, if you start working now, you will work the rest of your life.” I took the job and, as usual, Daddy was right.

When I was in the USAF and came home on leave, Daddy and I would walk to a local bar, have a few beers, a few cigarettes, and talk.

After I left the Air Force, we continued those visits to the bar and our talks until I moved to New York in 1965, working for IBM.

On my summer vacations while with IBM, my wife and I went to Huntington until after my mother died. Daddy and I spent many hours talking.

Our talks were something I shall always remember. Daddy was good at telling stories. I learned about a few funny incidents during World War I. (Daddy never spoke of the War except for humorous incidents.) I learned about my sisters growing up. I learned about my family’s good times. I learned about the Great Depression and hard times.

In those few short years I had with Daddy, I learned one heck of a lot. And more than just about the War and my family and hard times. I also learned about life and common sense.

Daddy was a very wise man.

Death

My father died in a veterans hospital on January 10, 1968, thirteen months after Mama died. He was not quite 74 years old.

During those thirteen months, Daddy visited me and my sisters. An interesting note here. Daddy turned nine years old the year that the Wright Brothers made their first flight, in 1903. Before he died, Daddy flew in a Boeing 707.

When Daddy was 72, he was still full of life and he had stories to tell. Daddy had dark, chocolate-brown hair and, in his sideburns, you could darned near count the gray hairs.

I have never witnessed such a transition in a man in so short a time period, the thirteen months following Mama’s death.

I saw Daddy six months after Mama died. The life was out of Daddy. No more stories to tell. No more laughter. His hair was completely gray.

Daddy had been transferred from the Huntington veterans hospital to a veterans hospital in Indiana. At the time of his death, none of the family were with him. Daddy died alone.

It was time to die.